LOS ANGELES—It is 8 p.m. on a soft spring Saturday and the oldest restaurant in Hollywood is packed to the gills. Tattooed hipsters in black jeans and miniskirts share the two bustling dining rooms with oldsters in cashmere V-necks, loafers, and Ferragamo pumps; jazzy standards pulse through the sound system at a volume neither too loud nor too soft; and the glow from the ancient wood-burning cast-iron grill suffuses the scene.

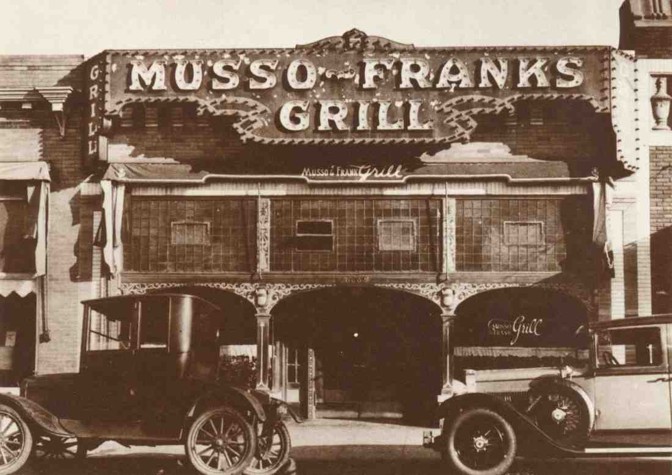

In this sprawling, polyglot culinary capital, where the cuisine ranges across the alphabet, from Armenian to Yemeni, the Musso & Frank Grill, which turns 100 years old in September, has not only endured but also prevailed, with a menu that still features such antique dishes as Welsh rarebit, chicken pot pie, grilled lamb kidneys, and calf’s liver with onions, not to mention its spine-tingling, stirred-not-shaken martinis—55,272 of them served last year alone.

Los Angeles’s food scene has never been hotter. The Michelin Guide recently announced plans to resume reviewing restaurants here after a nine-year hiatus occasioned by the feeling that the city’s restaurants weren’t quite up to snuff? The Los Angeles Times has just relaunched a stand-alone food section to explore the city’s burgeoning restaurant culture each Thursday? The New York Times has dispatched its first-ever California food critic, Tejal Rao, to sample the region’s bounty?

None of that much matters at Musso’s, whose mahogany booths and original hat stands would feel instantly familiar to Charlie Chaplin, F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, Raymond Chandler, Orson Welles, Lauren Bacall, Elizabeth Taylor, Dorothy Parker, Alfred Hitchcock, or any of the dozens of others who made it one of the places to eat in Hollywood’s golden age—plus a raft of more recent regulars, including Gore Vidal, Keith Richards, and Quentin Tarantino, who features the restaurant in his forthcoming film, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Over the years, Musso’s has also made cameo appearances in many movies and television shows; it doubled as the New York theater hangout Sardi’s in Mad Men, for instance, and Kerry Washington ate there in an episode of Scandal.

Most of Musso’s contemporaries among the hot spots of old Los Angeles are long gone, including the Brown Derby (the inventor of the Cobb salad), Chasen’s (supposedly the birthplace of the Shirley Temple), and the Cock’n Bull (the cradle of the Moscow mule).

Yet Musso’s is thriving, and was recently featured favorably in one of Rao’s first reviews; she praised its “impossibly charming dining room,” and called the cocktails and steaks “unfailing” and the wedge salads “dignified.” By most accounts, the food—which was slipping a decade and more ago—is better than ever, and the restaurant has posted consistent double-digit revenue growth in recent years, according to Mark Echeverria, the chief operating officer in the fourth generation of family ownership.

Why? “I think Musso’s is in a time warp that appeals to our occasionally wanting to just strip away the new, the shiny, and the uncertain to simply eat and relax,” Barbara Fairchild, the former editor of Bon Appétit and a longtime Angeleno, wrote me in a recent email. “You don’t come to Musso’s to prove a point. You just come to enjoy yourself.”

As Fairchild also pointed out, “L.A. is an explosion of flavor right now, and our restaurant scene is booming, the best, most diverse in the country,” and diners have nearly infinite options. So Musso’s—a restaurant so old that its “new room,” the overflow dining area and bar, dates to 1955—may be trading on nostalgia in a city “that a lot of people stereotypically think of as the Capital of the Ephemeral,” she said.

But the restaurant is trading on more than that, too. Its real secret is its constancy. It makes no nod to nouvelle cuisine or farm-to-table provenance (no waiter will ever tell you the name of your lamb or the farmer who raised it). But because Musso’s is in California, the avocados are always ripe, the tomatoes juicy, the lettuce fresh, and the vibe laid-back. The waiters—all men, in crisp, red waist-length jackets with black lapels—are professional and polished, and most of them have a tenure of many years, if not decades. Ruben Rueda, a legendary bartender who worked at the restaurant for 52 years beginning as a busboy and who used to drive Charles Bukowski home if the writer was drunk, died just last month.

The bartenders serve up Manhattans, sidecars, old-fashioneds, and those trademark martinis, which come in a frosty three-ounce glass (so the gin or vodka stays cold) with a carafe containing the second pour—the “dividend”—nestled in a miniature hammered, stainless ice bucket brought to your table. As for food, the basics are best, such as the daily specials, including short ribs and sauerbraten.

Sean Daniel, a veteran movie producer and studio production chief, first went to Musso’s as a young junior executive at Universal Studios some 40 years ago. “When I got an expense account, I literally was like, ‘I’ve always wanted to eat at Musso & Frank. I’ve never been able to afford it. That’s where I’m going,’” he recalls. “And I have to say, I think that was a ritual for many people.” Daniel still goes to the restaurant each September for an annual birthday lunch for his friend Frank Marshall, a producer, where the attendees include the director Bob Zemeckis and other old pals.

Musso’s future was not always certain. As its location on Hollywood Boulevard grew steadily seedier in the 1970s, ’80s, and early ’90s, it suffered along with the neighborhood. Twenty years ago, the main dining room could be a tomb on Saturday nights and reservations were never a problem. Finding a vegetarian dish wasn’t impossible, but it wasn’t easy either. I once shared a meal with Carole King in which she had to content herself with one bowl of stewed tomatoes and another of sautéed spinach. An aging second generation of management had cut corners and let quality slide, and as the Great Recession of 2008 loomed, the restaurant risked going under.

That’s where Echeverria, 39, enters the story. He is a great-grandson of John Mosso (no relation to the restaurant’s namesake), who with a partner, Joseph Carissimi, bought the place in 1927 from its first owners, Frank Toulet and Joseph Musso (the original name was Frank’s François Café). Together, Mosso and Carissimi presided over Musso’s glory days, even as newer, swankier places such as Romanoff’s in Beverly Hills competed for celebrity customers in the 1940s and ’50s. In 2009, with no third-generation family members involved in active day-to-day management, the Mosso heirs bought out the Carrisimi family and installed Echeverria, who had run fly-fishing lodges in Alaska and worked as an operations manager at a ski resort in Lake Tahoe during the winters, as chief financial officer and chief operating officer.

“I had some of the business operational experience that they were looking for,” he told me, “and they felt I had a value to bring.” Echeverria’s first goal was “to bring the quality of food and service back up to the standard of what our community expected from us,” all without changing anything too much. The restaurant’s first executive chef, Jean Rue—who held the job for 53 years—was French-trained, but his menu reflected the Continental melting pot that was early Hollywood, so there were classic French dishes, but also Italian specialties, Hungarian goulash, and Wiener schnitzel. “The menu started becoming this thing that everyone could relate to,” Echeverria said, and he was determined to carry on that tradition. He hired J. P. Amateau, a graduate of the Culinary Institute of America, as executive chef. As it happened, Amateau had a personal connection to Musso’s. His father, Rod Amateau, was Humphrey Bogart’s stunt double and later a director of television programs such as Starsky and Hutch, and a young J. P. often went with his father to savor the restaurant’s signature flannel cakes—large, thin, sugarless pancakes—at the grill counter.

In celebration of the centennial, Echeverria is opening three private dining rooms in a former retail space adjoining the barroom. But the cold-eyed key to Musso’s survival is that the restaurant’s owners are also its landlords (they’ve owned the building for decades), with a large valet parking lot in the rear so patrons can drop their car with ease and avoid the street scene on Hollywood Boulevard, which can still sometimes be as tawdry and vivid as anything Nathanael West described in The Day of the Locust.

By the end of my meal on that recent Saturday, at 9:50 p.m., there was still not an empty seat in the main dining room, where the V-shaped copper wall sconces cast a gentle light over the linen-covered tables and glinting glassware, and the murmur of satisfied eaters—first-timers and regulars alike—was the sound of people just happy to be in a place that still does what it does so well.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment